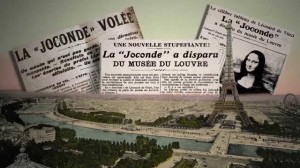

Era l’agosto del 1911 quando un imbianchino di Dumenza di nome Vincenzo Peruggia si rese responsabile del più grande furto d’arte di tutti tempi, quello della Gioconda di Leonardo dal Salon Carrè del Louvre. Su quest’uomo è stato scritto di tutto, almeno qui da noi, ma forse ancora di più sono state le leggende sviluppatesi nel corso del tempo che, amplificate dalle bocche di vecchie comari, si sono trasformate in strani fenomeni di campanilismo. Così, il cuore della vicenda, il furto, il tentativo di rivendita del quadro a un antiquario fiorentino, ma anche e soprattutto tutto quello che ci sta in mezzo, è passato inesorabilmente in secondo piano, e le gesta del Peruggia si sono fatte materia da racconto folcloristico, dove realtà e finzione si perdono nel delirio delle congetture. Pertanto la Monna Lisa, dopo essere stata trafugata dalla Francia, sarebbe persino giunta nel maccagnese, a Cadero, come sostiene uno strano feticista delle mutande che da quelle parti ci abita e che pare pure averci scritto un libro. Ogni varesino del nord ha adattato la vicenda alle proprie esigenze, alla propria terra, nel desiderio un po’ barbino di accaparrarsi l’esclusiva su una vicenda che di italiano ha forse molto poco, se non il presunto patriottismo del ladro che tentò di restituire alla nazione una parte del suo tesoro perduto. Per questo il documentario di Joe Medeiros lo si consiglia e va visto, perché fa chiarezza su tutto questo garbuglio di chiacchiere da paese, snoda e sbroglia la matassa del chi fu quest’abile imbianchino, perché fece quel che fece e come lo fece, e senza mai cadere nell’arabesco della supposizione. Medeiros, americano seppur di origine italiana, lavora appunto da americano, apre i libri, fa ricerche, consulta gli archivi e raccoglie testimonianze come un certosino dell’informazione. Restituendoci quindi la Storia del Peruggia, quella con la S maiuscola, scevra da abbellimenti, infiorettature o appropriazioni indebite da parte degli autoctoni. E quel che il nostro regista svela ha del miracoloso, dell’assurdo, qualcosa di così profondo che soltanto uno sciocco potrebbe perdere tempo a collocare il quadro di Da Vinci in un posto o nell’altro del varesotto, dove peraltro la Gioconda mai passò: Peruggia, che la perizia psichiatrica dichiarava un frenastenico, cioè un subnormale, riuscì in totale autonomia a trafugare la preziosa opera d’arte e a tenersela per circa un biennio nell’armadio della propria camera senza destare sospetti.

Era l’agosto del 1911 quando un imbianchino di Dumenza di nome Vincenzo Peruggia si rese responsabile del più grande furto d’arte di tutti tempi, quello della Gioconda di Leonardo dal Salon Carrè del Louvre. Su quest’uomo è stato scritto di tutto, almeno qui da noi, ma forse ancora di più sono state le leggende sviluppatesi nel corso del tempo che, amplificate dalle bocche di vecchie comari, si sono trasformate in strani fenomeni di campanilismo. Così, il cuore della vicenda, il furto, il tentativo di rivendita del quadro a un antiquario fiorentino, ma anche e soprattutto tutto quello che ci sta in mezzo, è passato inesorabilmente in secondo piano, e le gesta del Peruggia si sono fatte materia da racconto folcloristico, dove realtà e finzione si perdono nel delirio delle congetture. Pertanto la Monna Lisa, dopo essere stata trafugata dalla Francia, sarebbe persino giunta nel maccagnese, a Cadero, come sostiene uno strano feticista delle mutande che da quelle parti ci abita e che pare pure averci scritto un libro. Ogni varesino del nord ha adattato la vicenda alle proprie esigenze, alla propria terra, nel desiderio un po’ barbino di accaparrarsi l’esclusiva su una vicenda che di italiano ha forse molto poco, se non il presunto patriottismo del ladro che tentò di restituire alla nazione una parte del suo tesoro perduto. Per questo il documentario di Joe Medeiros lo si consiglia e va visto, perché fa chiarezza su tutto questo garbuglio di chiacchiere da paese, snoda e sbroglia la matassa del chi fu quest’abile imbianchino, perché fece quel che fece e come lo fece, e senza mai cadere nell’arabesco della supposizione. Medeiros, americano seppur di origine italiana, lavora appunto da americano, apre i libri, fa ricerche, consulta gli archivi e raccoglie testimonianze come un certosino dell’informazione. Restituendoci quindi la Storia del Peruggia, quella con la S maiuscola, scevra da abbellimenti, infiorettature o appropriazioni indebite da parte degli autoctoni. E quel che il nostro regista svela ha del miracoloso, dell’assurdo, qualcosa di così profondo che soltanto uno sciocco potrebbe perdere tempo a collocare il quadro di Da Vinci in un posto o nell’altro del varesotto, dove peraltro la Gioconda mai passò: Peruggia, che la perizia psichiatrica dichiarava un frenastenico, cioè un subnormale, riuscì in totale autonomia a trafugare la preziosa opera d’arte e a tenersela per circa un biennio nell’armadio della propria camera senza destare sospetti.  Eppure tutto in Peruggia faceva subodorare l’atto mancato, lo sberleffo involontario a quella cultura che tanto detestava gli immigrati italiani, come le impronte digitali abbandonate con noncuranza sulla cornice del quadro, i due arresti che già lo avevano costretto a soggiornare brevemente nelle prigioni di Francia e che lo trasformavano nell’indiziato numero uno. Medeiros fa vedere tutto questo con scanzonato disappunto, intervalla le interviste ai discendenti dell’imbianchino ai siparietti disegnati, le immagini alle animazioni, e ci chiede (si chiede) perché la polizia francese pretese le impronte digitali da tutti gli impiegati del Louvre tranne che da lui, che pure al Louvre ci lavorava come vetraio, perché andò a disturbarlo nella propria residenza senza nemmeno perquisire lo sgabuzzino dove la Gioconda era stata sbadatamente collocata. Mistero. Anzi no, surrealismo, proprio quello che da pochi anni a quella parte sarebbe diventato una corrente artistica, una moda parigina, e che avrebbe avuto proprio Apollinare tra i primi esponenti. Perché lo si cita? Perché sia lui che Picasso furono arrestati e interrogati in quanto indiziati del crimine. Due grandi uomini del Novecento europeo mutati da un imbianchino frenastenico in pericolosi sospettati, cosa che ha reso il Peruggia il personaggio inconsapevole di un film, che l’ha fatto diventare una sorta di Totò del nord, reo confesso di aver (quasi) rivenduto la Monna Lisa anziché la Fontana di Trevi. Certo quest’uomo geniale, ma di una genialità sottile e posta come dire in filigrana, non ha potuto beneficiare nemmeno di un riconoscimento postumo: una targa, se non quella appesa quasi in sordina sulla casa dei parenti, una statua, una via.

Eppure tutto in Peruggia faceva subodorare l’atto mancato, lo sberleffo involontario a quella cultura che tanto detestava gli immigrati italiani, come le impronte digitali abbandonate con noncuranza sulla cornice del quadro, i due arresti che già lo avevano costretto a soggiornare brevemente nelle prigioni di Francia e che lo trasformavano nell’indiziato numero uno. Medeiros fa vedere tutto questo con scanzonato disappunto, intervalla le interviste ai discendenti dell’imbianchino ai siparietti disegnati, le immagini alle animazioni, e ci chiede (si chiede) perché la polizia francese pretese le impronte digitali da tutti gli impiegati del Louvre tranne che da lui, che pure al Louvre ci lavorava come vetraio, perché andò a disturbarlo nella propria residenza senza nemmeno perquisire lo sgabuzzino dove la Gioconda era stata sbadatamente collocata. Mistero. Anzi no, surrealismo, proprio quello che da pochi anni a quella parte sarebbe diventato una corrente artistica, una moda parigina, e che avrebbe avuto proprio Apollinare tra i primi esponenti. Perché lo si cita? Perché sia lui che Picasso furono arrestati e interrogati in quanto indiziati del crimine. Due grandi uomini del Novecento europeo mutati da un imbianchino frenastenico in pericolosi sospettati, cosa che ha reso il Peruggia il personaggio inconsapevole di un film, che l’ha fatto diventare una sorta di Totò del nord, reo confesso di aver (quasi) rivenduto la Monna Lisa anziché la Fontana di Trevi. Certo quest’uomo geniale, ma di una genialità sottile e posta come dire in filigrana, non ha potuto beneficiare nemmeno di un riconoscimento postumo: una targa, se non quella appesa quasi in sordina sulla casa dei parenti, una statua, una via.

Colpa della legge, più surreale della vicenda, che vieta il pubblico elogio a chi ha subito un processo penale. Peccato che non impedisca la conservazione di una frase di Mussolini nella piazza di Dumenza. In fin dei conti, lui il processo non lo subì proprio, se non sommariamente…

Marco Marchetti

Mona Lisa is Missing

Regia: Joe Medeiros. Fotografia: Joe Medeiros, Fabio Pasini. Montaggio: Leonard Feinstein, Joe Medeiros. Musica: Brian Langsbard. Origine: USA, 2012. Durata: 85′.

English version

August, 1911. A house painter from Dumenza, Vincenzo Peruggia, made himself the head of the greatest art robbery of all times, stealing Leonardo’s Gioconda from the Salon Carré, at the Louvre museum. A lot has been written about this man, or at least here in Italy, though – maybe – even more has been told as tales and legends, here and there, legends which got enriched – through time – by those who talked about it.

This way, the heart of the real story, the theft, the try to resell the painting to a Florentin ancient dealer, and – above all – everything that lies in the middle, has been moved to the background, and what Peruggia did for real was transformed in a folkloristic tale, where reality and fiction get lost in the fury of conjectures. The Monna Lisa, then, after it has been smuggled from France, has probably arrived in the area of the small city of Maccagno, in Cadero to be specific, though these are just the indications of a panties fetishist who lives in the area and who appears to have also written a book about that.

Every italian has adapted the story to his own needs in order to get a little of fatherhood on a story which of Italian has barely nothing, if not the presumed patriotism of a thief who was willing to give back to his nation one of its lost treasures. Here’s the reason why Joe Medeiros‘ documentary should be watched, because it enlights the dark in this confused and entangled mess of chatting, because it disentangles that mess and shows who really was this house painter and why he did what he did, without ever falling in hypothesis. Medeiros, american though of Italian origin, works in fact as an american would do. He opens the books, makes researches and consults the archives and collects testimonies as a careful journalist. Giving us back Peruggia’s real story, then, free from any decoration added during the years and from the undue fatherhood, what the director reveals shows something miracolous and absurd, since no one would have ever thought that Da Vinci’s masterpiece may have been hidden in the neighborhood of Varese, Italy. Peruggia, who had been defined by the psychiatric report a “subnormal” managed, completely autonomous, to smuggle the famous painting and to keep it for almost two years in his wardrobe without being suspected. In any case, everything in Peruggia’s behaviour leads us to think to a joke played to the French nation and reclaimed, by leaving his fingerprints on the painting frame for example. He was the first person to be accused, especially considering the fact that he had also been arrested twice in France, but, though, Medeiros shows us how the entire situation doesn’t appear that simple. He alternates the interviews to Peruggia’s relatives with images and animations and asks – to us and to himself – why did the french police demanded the fingerprints of every employee working at the Louvre Museum but Peruggia’s? Why did they bother him in his house without even looking in the specific place where the Gioconda was hidden? That’s a mistery. Or better, Surrealism, that kind of surrealism that in a few years from then would have become an artistic movement, and which would have had Apollinarie among his exponents. Why is he quoted? Because both him and Picasso were arrested and questioned about the crime. Two great men belonging to the european 20th century transformed by a “subnormal” house painter into potential suspects, aspects that made Peruggia the unaware lead character of a movie, making him a sort of new Totò of the north, guilty of having (almost) sold the famous Monna Lisa instead of the Trevi Fountain.

This incredible man has not even had the benefit of a statue or a street with his name, but the fault is of the law, more surrealistic than the story itself, since it forbids the celebration of a person who’s been penally tried. Though, it’s a shame that it doesn’t forbid the conservation of a quotation by Mussolini in Dumenza Square. Even if, actually, he was never been tried in front of a judge, if not quite roughly.

(traduzione di Mattia Serrago)