INTERVIEW WITH PIERRE BISMUTH (English version)

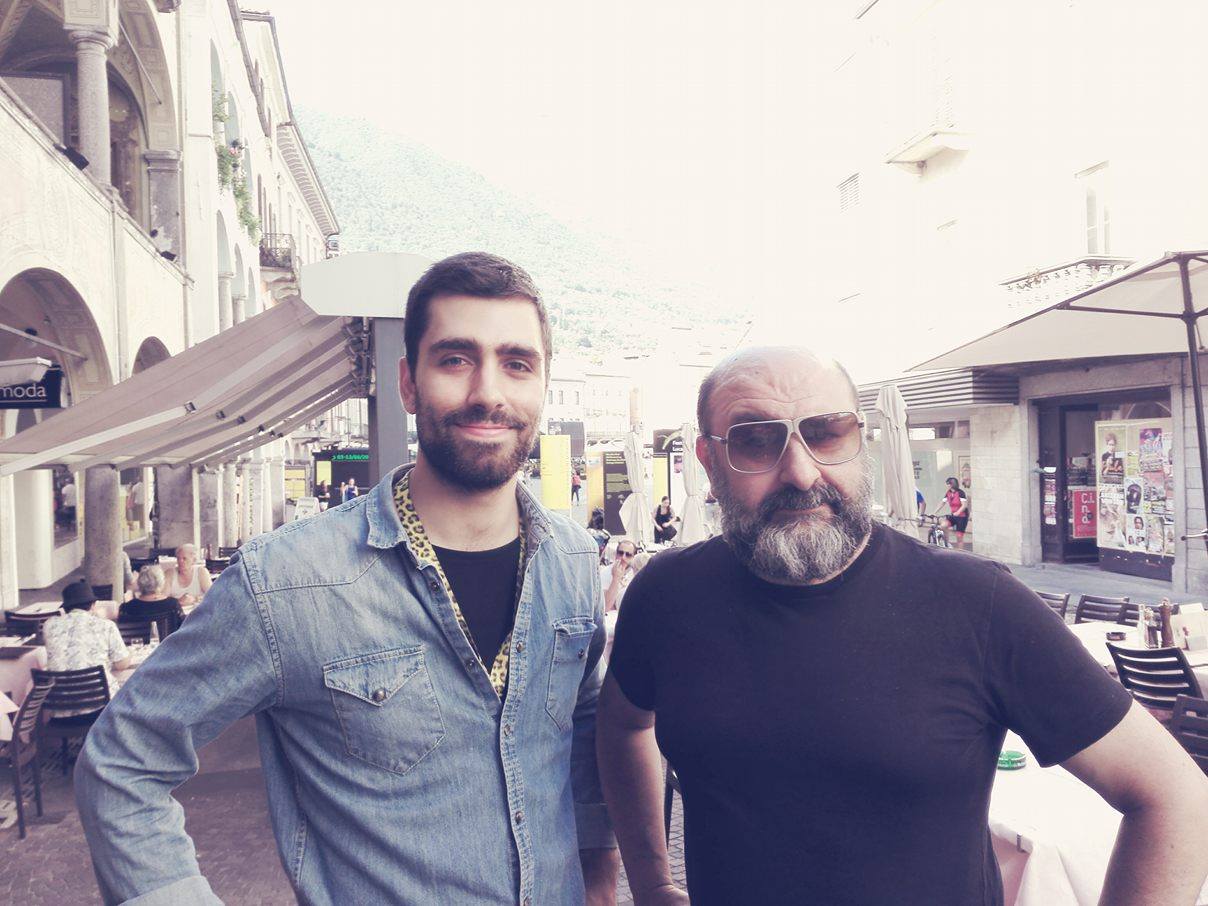

At the International Locarno Film Festival, this year, we met a great and incredibly original personality; one of the minds behind the movie which won the Academy Award for Best Screenplay, The Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind: Pierre Bismuth.

At the International Locarno Film Festival, this year, we met a great and incredibly original personality; one of the minds behind the movie which won the Academy Award for Best Screenplay, The Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind: Pierre Bismuth.

We had the opportunity to talk with him about his new movie, “Where is Rocky II?”, presented at the 69th edition of Locarno Film Festival.

Bismuth’s new movie, clearly looking for originality, focuses on the investigation of a piece of art known as Rocky II, made by the famous artist Ed Ruscha and whose location remains unknown.

Portraying a real documentary disguised as a fiction, Bismuth tells us about his research and investigation to find the mysterious rock.

M. S. : Pierre, what can you tell us about The Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, the movie that made you known as a great scriptwriter?

P. B. : Well, at that time I was just being kind to Michel Gundry. He was always interested in my ideas.

For what concerns the idea behind The Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind we met very informally for a brainstorming on the story, which he liked a lot. After that he just asked me if I could write a page on that and I did it. Four…no, Seven years later, they told me that they were ready for the movie.

M.S. : Now, let’s get to “Where is Rocky II?”

How did you manage to put together three different stories in it?And I say “three different stories” because we have:

– the reality plan, the real life, therefore you investigating on Ed Ruscha’s work;

– the fake fiction, which is the movie you made on this investigation in a documentary style disguised like a real movie;

– the parallel story of the screenwriters Peckham and DeVincentis, writing another movie based on the investigation you’re running in the film.

P. B. : No, it’s not that complicated. There are just two story layers:

– a documentary part: which is not only about the investigation I was running. It is also about the screenwriters writing a new film based on the investigation itself;

– a fiction part: that is only a visualization of what the research and their writing were.

M. S. : It’s really interesting the way you approached the documentary style. What we see doesn’t remember at all the features of a documentary, but, rather, those of a fiction. So the real story is told like a real film.

P. B. : Yeah, my idea was to shoot a real documentary, but in such a way that it would have looked fictional. We’re actually on stage, filming the entire process, but it’s not acting. All the conversations we had were made out of a single shot. No restaging. Maybe just a few times just to change the camera.

Early on, my problem in making this movie was the story behind it.

I knew about this piece, Rocky II, but the real obstacle was making this story believable, and in order to do that I needed Ed Ruscha to admit that the piece actually existed.

When I looked for information on Rocky II on Internet I couldn’t find anything, so I went to the press conference that we see at the beginning of the movie and I asked him “Where is Rocky II?”; then his reaction was honestly better than I could ever expect. Admitting the existence of Rocky II, he gave me the possibility to start working on the movie.

From that moment I thought that I could start investigating by myself, but I had a problem. I couldnt’ orientate myself in L. A. or in the Mojavi desert; that’s why I decided to hire a private detective, since L. A. is plenty of them and, moreover, the figure of the private detective turned out to be useful to add to the movie that sense of fiction that I needed to transform the documentary part into a real film.

At this point I was interested in answering two questions:

– Where is that piece? Since the location is unknown;

– Why did he do that piece? Since, to me, it was impossible finding a reason to explain why an artist would make a piece – on which by the way the BBC shot a documentary – just to keep it hidden from anyone, refusing to talk about it.

M. S. : Well, for sure the idea of the detective turns out to help the fiction very much…

P. B. : Yeah, it’s true, but very soon I realized that, though the detective could actually help me find the piece, he couldn’t help me understand why?

I thought, then, who else could solve the problem of the second question – therefore, the motivation behind the creation of the piece – and eventually I realized that that was the job of the screenwriter.

It was the investigation of the “why?” that led me to involve the screenwriters in the process.

M. S. : What’s your relationship with Ed Ruscha at the moment?

P. B. : I have no relationship with Ed Ruscha. He was not involved in the movie because I wanted the research to be real. I just sent him an e-mail saying something like: “We’re gonna shoot the film, we’re gonna go to people you know. Hope you don’t mind…”

M. S. : One important thing in the movie is that, though you merge the fictional and the documentary parts in a single film, there’s no prevailing of one of these part on the other, which made me think: how important is it to get good actors in these kind of movies? Since it’s because of them that such a balance is obtained…

P. B. : Well, it’s always better to have the best actors possible. In this case we had very little time to make the actors get into the mood, but they did great. Those guys are professional.

M. S. : And what about the scenes where the screenwriters talk about the realization of the movie?

P. B. : That’s all spontaneous. There was no connection between them and the actors. They just talked with me because I was feeding them with information on the investigation of Rocky II to allow them to write a good script on the other film based upon the research.

M. S. : It is also interesting how you portrayed the world of scriptwriters Pierre, the process of creation and the dropping of ideas. That’s something which is rarely explained in movies.

P. B. : Yeah, and there’s also a lot of this in the scene where Mike White comes in the house where DeVincentis and Peckham are working to give them advices on the possible teaser trailer. That identifies perfectly the dropping of ideas and the process of movie construction from the screenwriter’s point of view.

M. S. : Pierre, before being a scriptwriter or a movie-maker, you’re known as an artist. Is it right to say that there’s a lot of art in this movie?

For example we have scenes which are connected not only by the narration path, but also by the colors present in those scene, by the music of those scenes… we could say, for instance, that sometimes landscapes refer to a specific kind of music and that music refer to a specific kind of landscape…

P. B. : Yeah, you’re right. That’s a good point. The music worked exactly like you said.

INTERVISTA A PIERRE BISMUTH

Al Festival di Locarno, quest’anno, abbiamo incontrato una personalità stravolgente e incredibilmente originale; una delle menti dietro al film premio Oscar alla Miglior Sceneggiatura The Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind: Pierre Bismuth.

Con lui abbiamo avuto modo di parlare del suo nuovo progetto, “Where is Rocky II?”, presentato proprio alla 69° edizione del Festival di Locarno.

Il nuovo film di Pierre Bismuth, chiaramente incentrato sull’originalità, si concentra sulla lunga ricerca di un’opera d’arte chiamata per l’appunto Rocky II, creata dal famoso artista Ed Ruscha, e la cui ubicazione resta ignota.

Ritraendo un reale documentario nelle vesti di un vero e proprio film, Bismuth ci racconta il processo d’investigazione a caccia della misteriosa opera.

M. S. : Pierre, cosa puoi dirci in merito a The Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, il film che ti ha reso conosciuto come un grande sceneggiatore?

P. B. : Beh, a quei tempi stavo collaborando con Michel Gundry. Lui era molto interessato alle mie idee.

Per quanto riguarda l’idea alla base del film The Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (Se mi lasci ti cancello) ci incontrammo in tono molto informale per effettuare un po’ di brainstorming sulla storia, storia che a lui piacque molto. Dopo aver organizzato le idee mi chiese se potessi stendergli qualche pagina di soggetto e io lo feci. Quattro… no, sette anni dopo, mi dissero che era tutto pronto per la realizzazione del film.

M. S. : Spostiamoci, ora, su Where is Rocky II?

Come sei riuscito a mettere insieme tre storie diverse? E dico “tre storie diverse” perché abbiamo:

– un piano reale, che fa capo alla vita reale, e quindi alla ricerca che hai realmente condotto sul lavoro dell’artista Ed Ruscha;

– la cosiddetta fake-fiction, vale a dire il film che hai tratto dalla reale ricerca di “Rocky II”, girato in uno stile documentario, ma mascherato nelle vesti di un film.

– la storia parallela degli sceneggiatori Peckham e DeVincentis, impegnati alla realizzazione di un altro film, basato sull’investigazione che è fulcro di questa pellicola.

P. B. : No, non è così complicato. Ci sono solo due piani:

– un piano documentario: che non consiste solo nell’investigazione che conducevo, ma che tratta anche del processo di scrittura degli sceneggiatori impegnati a scrivere un nuovo film basato sull’investigazione stessa;

– una piano in stile “fiction”: vale a dire la messa in camera, la visualizzazione dell’investigazione e della fase di scrittura degli sceneggiatori.

M. S. : è molto interessante il tuo approccio allo stile documentario. Quello che vediamo, di fatti, non ne ricorda per niente le caratteristiche, assumendo piuttosto, i tratti di un film vero e proprio.

P. B. : Sì, l’idea era quella di girare un vero documentario, ma in modo da farlo apparire finto, come un film a tutti gli effetti. Siamo effettivamente sul set e filmiamo tutto, ma non c’è recitazione.

Tutte le conversazioni che abbiamo avuto sono state frutto di una singola ripresa. Non c’è stato alcun restaging. Forse solo un paio di volte, ma solo per spostare la camera.

Inizialmente, il mio problema nel fare questo film era la storia che vi era dietro.

Ero a conoscenza di quest’opera d’arte, Rocky II, ma il vero ostacolo era rendere la sua storia credibile, e per farlo avevo bisogno che Ed Ruscha, l’artista suo creatore, ne ammettesse l’esistenza.

Quando cercai informazioni su Rocky II su Internet non riuscii a trovare nulla, quindi decisi di recarmi alla conferenza stampa che vediamo all’inizio della pellicola per chiedere a Ruscha dove fosse effettivamente l’opera.

In tutta onestà la sua reazione fu migliore di quanto potessi aspettarmi. Ammettendo l’esistenza di Rocky II, Ruscha mi diede la possibilità di iniziare a lavorare al film.

Da quel momento in avanti pensai di poter iniziare a investigare per conto mio su dove fosse la famosa roccia, ma avevo un problema: non sapevo come orientarmi, né a Los Angeles, né nel deserto del Mojavi, dove si dice che l’opera sia nascosta. Fu allora che decisi di incaricare della ricerca un investigatore privato, dato che L. A. ne è piena. E poi, in aggiunta, la figura del detective risultava essere più che utile ad aggiungere al film quel senso di fiction necessario a mascherare lo stile documentario.

A questo punto ero interessato a rispondere a due domande:

– Dov’è l’opera? Dato che la sua ubicazione è sconosciuta;

– Perché Ruscha ha voluto creare una simile opera? Per me era impossibile comprendere il perché un artista avesse messo al mondo una creazione – sulla quale, peraltro, la BBC sviluppò anche un documentario – per poi nasconderla, rifiutandosi, inoltre, di parlarne apertamente.

M. S. : Beh, di certo l’idea del detective risulta essere effettivamente utile per la fiction…

P. B. : Sì, è vero, ma presto ho realizzato che, nonostante il detective potesse aiutarmi nel trovare l’opera, questi non avrebbe comunque potuto rispondere alla mia seconda domanda: il perché dietro la creazione dell’opera stessa.

Pensai, pertanto, a chi potesse aiutarmi a risolvere il problema della seconda domanda e, infine, ho realizzai che l’investigazione che mi serviva era compito degli sceneggiatori. La ricerca è il primo compito di uno sceneggiatore. Fu questo che mi spinse a coinvolgere Peckham e DeVincentis.

M. S. : Qual è la tua relazione con Ed Ruscha al momento?

P. B. : Non ho alcuna relazione con Ed Ruscha. Non l’ho coinvolto nel film perché volevo mantenere quanto più reale possibile la mia ricerca. Gli ho semplicemente inviato una mail dicendogli qualcosa come: “Gireremo un film su di te e incontreremo persone che conosci… Spero non ti dispiaccia”.

M. S. : Un fattore importante nel film è che, nonostante tu riesca a fondere lo stile fiction con quello documentario in un unico film, non si percepisce il prevalere di uno stile sull’altro; questa considerazione mi ha fatto pensare: quanto è importante avere bravi attori in questo genere di film? Poiché è grazie a loro che si ottiene questo equilibrio.

P. B. : Beh, è sempre meglio avere i migliori attori possibili. In questo caso abbiamo avuto pochissimo tempo per far sì che gli attori entrassero nel giusto mood, ma se la sono cavata alla grande. Sono professionisti.

M. S. : E per quanto riguarda le scene dove gli sceneggiatori discutono in merito alla realizzazione del film?

P. B. : è tutto spontaneo. Non c’è stato alcun collegamento tra loro e gli attori. Parlavano solo con me perché chiaramente io li aggiornavo con le info in merito alla ricerca su Rocky II per permettergli di stendere una buona sceneggiatura sul film che avrebbero tratto dall’investigazione stessa.

M. S. : è anche interessante il modo in cui hai ritratto il mondo degli sceneggiatori Pierre, il processo di creazione e di maturazione delle idee. È qualcosa che viene raramente spiegato e illustrato.

P. B. : sì, c’è molto del mondo dello sceneggiatore nella scena in cui Mike White entra nella casa dove DeVincentis e Peckham stanno lavorando per dargli qualche consiglio in merito a un possibile trailer.

Quel momento identifica perfettamente la stesura delle idee e il processo di costruzione filmica.

M. S. : Pierre, prima di essere uno sceneggiatore e un regista, tu sei conosciuto come un artista. É giusto dire che ci sono numerosi stratagemmi artistici in questo film?

Per esempio, ci sono scene che non restano connesse unicamente dal filone narrativo, ma anche dai colori presenti nelle inquadrature e dalla musica in esse presente. Potremmo dire, per esempio, che talvolta, una determinata inquadratura di un paesaggio riesce quasi a riferirsi a un particolare scorcio musicale e che lo stesso brano si riferisca, viceversa, a quel dato paesaggio…

P. B. : Sì, hai assolutamente ragione! È un’ottima osservazione. Con la musica ho lavorato esattamente in questo modo.

Intervista a cura di Mattia Serrago